Education

As inspired by Clarence M. Haring, the first dean, teaching has been and continues to be "done by a faculty…challenged through daily exercise in demanding research." Eminent faculty have been elected to the prestigious ranks of the Institute of Medicine, the American Association for the Advancement of Science and have joined other leading scientific and medical organizations, often taking on leadership roles.

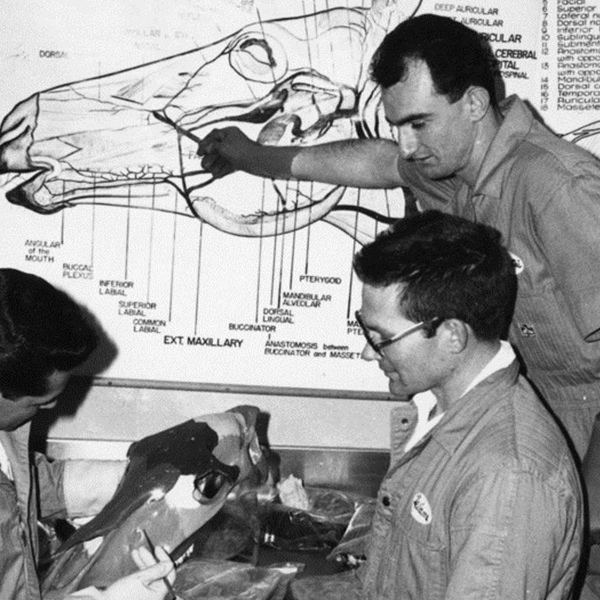

Forty-two men entered the first class of the school, graduating in 1952. Forty-one of the students, some older than their professors, had served in World War II and entered veterinary school with the support of the GI Bill.

By contrast with the all-male class of 1952, UC Davis women veterinary graduates in 1985 outnumbered men for the first time. The gender shift continued. In 2010, women represented 78 percent of all veterinary students.

Several women faculty and graduates broke gender barriers in academia. Included among these leading lights were Margaret E. Meyer, one of the first experts in veterinary public health; parasitology researcher Ming Wong, based at the California National Primate Research Center and described as a "passionate teacher" who composed 29 songs to help her students learn the names of parasites; and Virginia Perryman (DVM 1960), the first female veterinarian to be appointed chair in a veterinary school in Australia. Yet it was the 1990s when women faculty began regularly to head programs and gain significant recognition for innovative teaching—Jan Ilkiw and Alida Wind; creative comparative veterinary research—Fern Tablin, Linda Munson and Patricia Conrad; and global service—Jonna AK Mazet. In 1997, Mary Christopher received the national honor of the Zoetis (Norden) Distinguished Teacher Award, the greatest recognition in veterinary teaching. These women and their many colleagues provide strong role models for today's veterinary students.

As veterinary medical knowledge increased by leaps and bounds, faculty regularly and thoroughly reviewed the DVM curriculum to assure appropriate changes, technical innovations, organization and delivery of instruction to the adult student.

When the teaching hospital opened in 1970, faculty delivered an entirely new learning experience for fourth-year students. As the clinicians treated large and small animals owned by cooperating clients, students gained hands-on experience with a greater number and variety of real-world cases.

The teaching hospital facility also influenced the curriculum in another way. Traditionally, veterinarians prepared to enter practice immediately upon graduation by learning all areas of veterinary medicine. In the 1970s, the core-and-track schedule set a new standard for the four-year course of study. To the foundation of comparative medical knowledge provided in the curriculum's core, students added clinical experience in one of several species tracks. In this way, students in their fourth year began to focus on areas of professional interest and gain adequate experience for entry into practice.

Today's students integrate clinical experience into academic study starting with their first year. DVM candidates benefit from direct interaction with animals. Students observe at an early stage of their careers how academic principles apply to clinical practice. The third year, students receive state-of-the-art training in surgery, anesthesiology and patient management. Beginning with the class of 2015, to prepare students more fully for entry-level practice, clinical training in the senior clinical "year" of rotations expanded from 48 weeks to 59 weeks.

After the 1960s, veterinary medicine underwent two enormous shifts that influenced education. First, as science, technology and human medical advances became available, faculty developed previously unheard of veterinary medical disciplines and tailored those specialties to clinical practice. Secondly, veterinary practice found greater emphasis on small animals. Changes in the agricultural industry resulted in fewer farms with larger herds and flocks. Livestock practices evolved from the treatment of individual animals to a herd health approach. At the same time, clients with small animals were demanding more sophisticated treatments for their pets. Students learned about all these changes. They received exposure to the new veterinary specialties, gained more student experience with small animals and increasingly chose to emphasize small animals in the clinical year.

As the specialties blossomed, the teaching hospital in 1970 pioneered a residency training program with seven veterinarians seeking advanced clinical training from distinguished faculty. Residency training provided a path toward private practice, public service or academic veterinary medicine. The school is now the home of the largest residency program in the country, with more than 100 residents in 34 specialties.

The block format implemented with the Class of 2015 centers on students and educational theory regarding adult learning. Inquiry-based courses foster critical thinking, problem solving and communication skills. Recognizing that students learn in different ways, the curriculum features lectures, case-based learning, small group discussions and practical laboratory sessions.

Faculty have adopted 365 veterinary competencies with measurable outcomes. Each instructor collects and analyzes data to ensure that the curriculum is responsive to changes in the delivery of education and the needs of the veterinary profession.

With the explosion of scientific knowledge to be covered in four years, instructional technology has helped the faculty meet the challenge of efficient and effective teaching. From the earliest shared-view microscopes to slide presentations or video instruction to computer software, digital imaging, classroom "clickers" and electronic communication have streamlined instruction and encouraged self-paced study with prompt access to updates in veterinary medicine.

Technology supports independent study as well as real-time interaction with professors and classmates—whether in the same room or remote locations. Computers, PowerPoint and other software, mobile devices with specialized applications, and Web access to course content have supplanted outdated textbooks and cumbersome syllabi. The once-ubiquitous lecture format has been transformed into interactive webinars, course content, meetings, quizzes and small-group discussions in real time whether on site or remotely. All of the technology enhances the change to the faculty's new emphasis on case-based learning.

Student rotations at satellite programs in Sacramento, Tulare, San Diego and elsewhere provide broad career opportunities and meet the needs of students and residents with specific interests, particularly in food animal and zoological medicine.

Academic mentors since the earliest days of the school provided highly specialized education and mentoring for master's and doctoral degree candidates. Today, the school offers collaborative and interdisciplinary study through a variety of graduate groups. To assure that the pipeline of highly trained scientists is replenished each generation, faculty provide research experiences for veterinary students, graduate student support, a DVM-PhD program and other opportunities for veterinarian-scientists. Graduates become researchers, teachers and entrepreneurs.

To help veterinarians and veterinary technicians keep pace with constant changes in veterinary medicine, the continuing veterinary education program has met the needs of busy practitioners since the 1980s. School faculty host an annual clinical review, Web-based workshops and updates in such specialized fields as veterinary ophthalmology, nephrology and dermatology. Educational outreach also takes place through the Donald G. Low/CVMA Practitioner Fellowship, Veterinary Medicine Extension, student-run symposia, the Oscar W. Schalm Lecture, and lectureships for students, scientists and members of the public in epidemiology, nutrition, equine medicine and other topics.